By early 1967, American and allied forces appeared stuck in the morass of Vietnam. Publicly, military commanders talked about progress; off the record, Army officers told journalists that they weren’t “anywhere near the mopping up stage.” Moreover, the press increasingly noted Lyndon B. Johnson’s own frustrations. One report even suggested that the president was “tormented by the slow progress” of the war effort.

Ever an eye on domestic political trends, the president responded that spring by starting what would become a yearlong campaign to not only “sell” his Southeast Asia policy, but also disprove accusations of a stalemated war in Vietnam. Johnson began this publicity drive in April by bringing the head of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Gen. William Westmoreland, to report on the war’s progress. It was the first time in American history a president had called back a wartime field commander to testify on the administration’s behalf.

At the time, Westmoreland seemed the embodiment of post-World War II American military power. In naming Westmoreland its 1965 “Man of the Year,” Time magazine called the four-star general a “jut-jawed six-footer” and a “straightforward, determined man.” Westmoreland, already a veteran of two wars before arriving in Vietnam, had led the famed 101st Airborne Division and had served as West Point’s superintendent. In inheriting the multiple roles of a politically sensitive command in Vietnam, Time quipped, Westmoreland wore “more hats than Hedda Hopper.”

In 1965, however, Westmoreland had only one strategic goal in mind — arrest the losing trend. By most accounts, South Vietnam teetered on the verge of collapse. Hanoi was sending full infantry regiments along the infamous Ho Chi Minh Trail into South Vietnam. Acts of terrorism targeted local officials. The South Vietnamese Army (officially known as the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or A.R.V.N.) appeared incapable of keeping pace with the escalating levels of violence.

Westmoreland realized, though, that regaining the strategic initiative meant more than just killing the enemy. Rather, military operations were means to a larger end. In short, battlefield victories were intended to have political purpose.

Thus, throughout 1966 and early 1967, American forces undertook a host of missions helping to extend Saigon’s control over the population. They fought alongside the A.R.V.N. and local militia against enemy main force and insurgent units. They implemented nonmilitary civic action plans, such as medical visits to rural hamlets and administrative training of district officials. And they instituted programs to “win the hearts and minds of the people.”

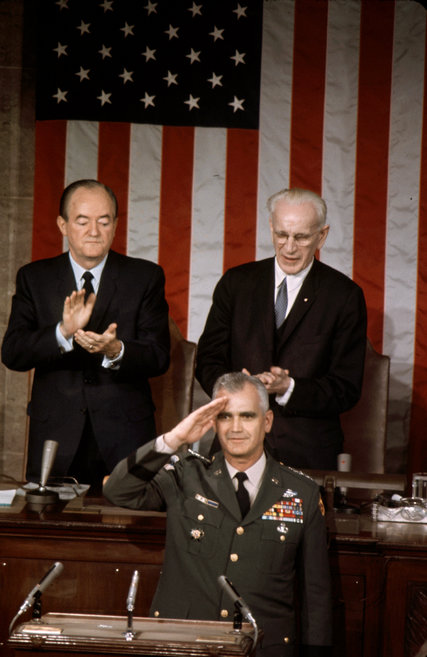

Gen. William Westmoreland appearing before a joint session of Congress in 1967. Credit Stan Wayman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Contrary to the way it was later portrayed in the press and history books, Westmoreland’s war proved far more than a singular focus on attrition of the enemy and racking up high body counts simply for a “false sense of military pride.”

Of course, there were myriad difficulties in implementing such a wide-ranging strategy, of balancing a war whose nature was as much political as it was military. Westmoreland grappled with contentious party politics in Saigon, with a Communist-nationalist message that resonated among the South Vietnamese countryside, and with a stubborn enemy committed to Vietnam’s reunification and freedom from Western influence.

Perhaps most troubling, by 1967 the American military command faced a home front increasingly questioning the sacrifices for a war that seemed to produce so few tangible results. As the year wore on, words like “stalemate” and “quagmire” became commonplace in appraisals of America’s strategy and chances for victory in Southeast Asia.

Westmoreland’s designation as the president’s chief surrogate in the spring of 1967, though, left little doubt that Johnson had committed himself, and the nation, to continued war. Johnson intended his “salesmanship campaign” to shore up defenses backing the United States’ commitment to Vietnam, to push back against those questioning the viability of his policies. The nation’s top field general would disprove critics by demonstrating progress.

At Westmoreland’s first stop, The Associated Press’s annual editors luncheon on April 25, the general argued that Vietnam’s fate would affect the future of all “emerging nations.” He lauded his soldiers’ performance in rescuing a Saigon government “on the verge of defeat,” while highlighting the complexities of this kind of war — “a war of both subversion and invasion, a war in which political and psychological factors are of such consequence.” And while a confident Westmoreland painted a favorable military picture, he twice emphasized a point that most likely made Johnson wince. “I do not see any end of the war in sight.”

Three days later Westmoreland gave another speech that overshadowed his A.P. address. To a joint session of Congress, the general roused legislators to “enthusiastic cheers,” according to one report, pledging that his command would “prevail in Vietnam over the Communist aggressor.” (Such language intimated a threat more external than internal.) Yet Westmoreland noted that military success alone would not ensure “a swift and decisive end to the conflict.” The enemy was waging a “total war all day — every day — everywhere.” Westmoreland maintained that only a strategy of “unrelenting but discriminating military, political and psychological pressure” on the enemy would lead to success.

At no time did Westmoreland mention the issue of stalemate. While their enemy was “far from quitting,” American forces, backed at home by “resolve, confidence, patience, determination and continued support,” would succeed.

Critics, though impressed by the general’s speech, believed Westmoreland had won no converts. Tom Wicker of The New York Times saw the oration as nothing more than a bid by Johnson to “enlist the general’s military prestige in the administration’s struggle to maintain political support at home.” And for all the plaudits he received, Westmoreland flew back to Vietnam having persuaded precious few in Washington.

Johnson’s salesmanship campaign fell short on two levels. Westmoreland did not convince the president’s opponents that American policy in Vietnam indeed was making progress. Nor, perhaps more important, did these speeches cause the American public to embrace the complex realities of the continuing war in South Vietnam.

In truth, Westmoreland proved unable to articulate the convoluted nature of a struggle over Vietnamese national identity that no foreign entity was likely to resolve. The war remained as “undefinable” as ever.

As 1967 unfolded after Westmoreland’s return to MACV headquarters, more and more evidence surfaced that the war might indeed be mired in stalemate. Pundits lambasted the quality of South Vietnam’s fighting forces. The pacification program appeared “tottering on the brink of collapse.” A political shake-up in Saigon — by 1967, a common occurrence to weary American officials — seemed to reflect security woes in the countryside. By year’s end, the battle over measuring “progress” seemed to rival the ferocity of the war itself.

Such debates aside, Westmoreland’s public statements in April 1967 offer a useful perspective on how Americans talk about war, particularly the strategies designed to win them. Throughout his tenure in Vietnam, Westmoreland wrestled with how best to communicate, to numerous and varied audiences, the complexities of a war so unlike the conventional battlefields of World War II. As one United States Embassy official in Saigon admitted, “I cannot make any positive statement about Vietnam that I cannot honestly contradict with another statement.”

But if the American war in Vietnam was truly “unlike anything else in the experience of our country,” 50 years on, it still can remind us of the need to embrace the nuances of war.

War is chaotic and messy. It defies easy explanations. And yet we turn to clichés all too often. In reality, for Vietnam, longstanding tropes like “body counts” and “attrition,” a mainstay of the historical narrative, have done little to advance a deeper understanding of what was always a complicated political-military affair.

How we — as politicians, as journalists, as historians, as the general public — talk about war, then and now, matters. Reducing complex wars to one-word phrases — Vietnam as war of “attrition” or supposed successes in Iraq as a result of a “surge” — dangerously oversimplifies. Rudimentary language dismisses the inherent chaos central to the deadliest of human endeavors. Easy explanations for victory and defeat make it hard to understand what really happened, and makes us less ready to understand the next conflict.

And in the end, simplifying war allows us to turn to it far more readily than we probably should.

NYT/The Opinion Pages/By Gregory Daddis an associate professor of history at Chapman University and the author of “Westmoreland’s War: Reassessing American Strategy in Vietnam.”